By Fredrik Sträng

How do you react when someone says it’s impossible, that it can’t be done, that it’s too hard or meaningless? Do you simply nod in agreement, avoid the debate, or perhaps turn a deaf ear? Having grown up in Närke—also known as the “whining belt”—I’m accustomed to the pessimistic refrain: “It will never work.” Yet I’ve learned a powerful way to handle this: to calmly and firmly ask, “What evidence do you have for that?”

Today, we’re going to dive deep into how we sometimes mentally slip into accepting a “no” far too easily, and how we let our surroundings influence our mindset. Best of all, I’ll share concrete tips on how we can navigate these negative spirals and spark a positive change. Join me—it’s time to take control of our thoughts and stand up to pessimism. Together, we’ll reach new heights!

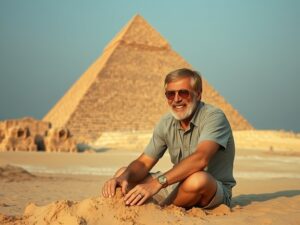

Image: Fredrik Sträng on the ridge of Lobuche East in Nepal with Mount Everest and Nuptse in the background.

Everything Seems Simple When I Return from an Expedition

Climbing in the harshest environments of the Himalayas is a journey that tests your body, mind, and soul. Every step and every breath at high altitude demands absolute presence. Expedition life is grueling—two months of physical exhaustion and mental challenges—but at its core, it is surprisingly simple. There are no distractions, only one focus: safety, food, sleep, and climbing. The contrast to the intricate puzzle of everyday life is striking when I come home. At home, water flows straight from the tap—while on the mountain, it takes 30 minutes to melt snow into a liter. Electricity is reliable and inexhaustible in daily life, yet on expedition, solar panels must fight against cloudy skies. Returning home makes it clear how much we take for granted—from reliable transportation to comfortable temperatures. Still, this simplicity, which should be a source of joy, often loses its radiance in the dullness of everyday routine. Why? Because we too easily fixate on what isn’t working—small setbacks that disturb our mental balance.

The Perspective from Setbacks

To truly understand and appreciate life’s comforts, sometimes we must experience their opposite. Research by Dr. Martin Seligman, the founder of positive psychology, shows that hardships and difficulties can lead to a phenomenon known as “post-traumatic growth.” In other words, people who endure demanding experiences often emerge stronger, more grateful, and with a deeper appreciation for life. This is exactly what an expedition provides—a chance to put everything in perspective. On the mountain, I expect resistance. I accept it as part of the journey without wasting energy lamenting the inevitable. That’s why it’s so ironic that, despite all these challenges, life on the mountain can feel far less complicated than life at home. And when I finally return, I feel a deep joy and gratitude for everything that makes our everyday life so comfortable—a feeling I wish more people could experience.

Your Challenge

Here’s your task: take one day to create a two-column list. In the left column, write down everything that works—from the moment you open your eyes in the morning: you wake up, you breathe, you have a bed, clean water from the tap, food in your fridge, and so on. In the right column, note what isn’t working—maybe spilled coffee, a late bus, or that your favorite fruit is out of stock at the store. Once you’re done, review the lists. I dare say that the left column will be significantly longer than the right. So why do we often get fixated on the contents of the right column? It partly comes down to our brain’s design. Psychological research—such as Daniel Kahneman’s work on “negativity bias”—demonstrates that we are hardwired to give greater weight to negative events than to positive ones. This was a survival instinct for our ancestors, enabling them to quickly identify threats. Yet in today’s world, it also causes us to overlook the abundance of good around us. A study from the University of California, Berkeley, even emphasizes that people who overcome difficulties often develop a stronger ability to appreciate the positive aspects of life (Emmons & McCullough, 2003). It is these challenges that provide perspective and help us recognize the value in things we previously took for granted. An expedition—with all its trials—embodies exactly that: a journey that not only tests you but also renews your appreciation for life’s simplicity and richness.

Reflection

Learning to appreciate the simplicity of everyday life is about retraining our mindset. Sometimes, we must step out of our comfort zones—to challenge ourselves, put ourselves in tough situations, and test our limits. Only then can we truly understand how much we have to be grateful for. Life is a celebration, but sometimes we need gentle reminders to see it that way. And perhaps, just perhaps, it’s time for you to embark on a small “expedition” in your own life—whether that’s a physical journey or a mental transformation.

The Chinese Farmer

Once upon a time, there was a Chinese farmer whose horse ran away. That very evening, all his neighbors came to offer their condolences. “We are so sorry that your horse has run away. This is very unfortunate,” they said. The farmer replied, “Maybe.”

The next day, the horse returned, bringing with it seven wild horses, and that evening, the neighbors exclaimed, “Oh, isn’t that lucky! What a wonderful turn of events—you now have eight horses!” The farmer again replied, “Maybe.”

The following day, his son tried to tame one of the wild horses, but while riding it, he was thrown off and broke his leg. The neighbors lamented, “Oh, what a shame,” and once more, the farmer said, “Maybe.” Then, the day after, conscription officers arrived to recruit men for the army, but they turned his son away because of his broken leg. Again, the neighbors declared, “Isn’t that great?” and once again, he replied, “Maybe.”

The entire process of nature is an intricately integrated one, and it is truly impossible to definitively judge whether an event is good or bad—because you never know what consequences may follow a mishap, or what the effects of good fortune will be. – Alan Watts

We are quick to label certain situations as “bad” if we dislike them, and “good” if we like them. Yet this binary way of thinking does not always serve us well. Today, we see this approach taking hold in our culture, with people and groups taking sides. Equally damaging is the tendency to draw hasty (sometimes overly hasty) conclusions about the effects or benefits of certain situations. You may launch a new venture, lose a key employee, witness market fluctuations, experience a computer crash, receive unexpected investments, see your managers at odds, or face a pandemic like COVID. Is it good? Bad? Maybe. One certainty remains: life is unpredictable. We never know what it might become—good, bad, or something entirely different. No matter what happens, the consequences are never clear-cut. Our work lives can resemble an emotional roller coaster. When confronted with emotionally charged challenges, we tend to frame situations in binary terms—as if everything must be resolved with one definitive answer.

Overcoming a binary mindset means learning to see beyond one option or the other. It requires us to pause and resist the urge to jump to conclusions. The tension wrought by polarization hides a critical opportunity for growth. If we can sustain that tension long enough, we can open ourselves to a third dimension—the realm of exploration, where creative solutions and compromise thrive. It is here, my friends, that true possibilities reside.

“You never know what may follow from a disaster, or what the consequences of good fortune will be.” – Alan Watts

The next time someone insists that something is impossible, ask, “What evidence do you have for that?” And when that inner voice whispers, “I can’t do this,” ask yourself, “What evidence do I have to believe that?” Challenge your assumptions, question your limitations—you are often stronger than you think.

Good luck with the challenge of the list!

——————————————————————

About Fredrik Sträng: Fredrik, in his leadership role, has summited seven of the world’s fourteen 8,000-meter peaks, set a Guinness World Record, and lectures on leadership, communication, decision-making, and crisis management.

Kind regards,

Fredrik Sträng

Climber – Speaker – Coach